St Francis of Assisi

Roman Catholic Church, Grosvenor Street, Chester, CH1 2BN, UK

Franciscans In Chester: St Francis' Church and Friary By Peter Bamford and Bernard Beatty

Contents:

| Preface | Acknowledgements and Introduction |

| Chapter One | Origin, Organisation and Life of the Franciscans |

| Chapter Two | The English Franciscans and The Restoration of the Friars |

| Chapter Three | The Franciscans Return to Chester |

| Chapter Four | Timber, Bricks and Mortar |

| Chapter Five | Growing Responsibilities |

| Chapter Six | St Francis's School |

| Chapter Seven | The Parish Club |

| Chapter Eight | More On Mission |

| Chapter Nine | Daughter Churches |

| Chapter Ten | Work with the Homeless |

| Chapter Eleven | Modern Times and Twenty-first Century Developments |

| Chapter Twelve | Guardians of Chester Friary and Parish Priests of St Francis' |

Preface - Acknowledgements and Introduction

Any work like this has of necessity to draw on its predecessors, and the authors gladly recognise their debt to 'Catholicism in Chester: A Double Centenary, St Werburgh's and St Francis's 1875-1975' by Sister Mary Winefride Sturman, OSU and 'St Francis - Chester: Brief History' by the late Father Crispin Jones OFM Cap.

Our thanks are due in particular to Miss Ellen Byrne and to Noel St John Williams for information on St Francis's School. We would also like to express our gratitude to the parishioners (too numerous to mention individually) who provided us either with items of information or with photographs which they were willing to allow to be copied. Unfortunately, lack of space prevented us from using more than a fraction of them. We apologise for this, and also for any factual errors, for which the responsibility is entirely ours.

This book was originally published in 2000 to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the consecration of St Francis’s church in Chester and the 125th anniversary of its opening. We begin with a guided tour to the church itself and then set out something of the Catholic and Franciscan history which gave rise to the church, friary and parish. The present parish of St Francis came about as a result of the revival of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850 but it is also a Capuchin and Franciscan house. So we cannot understand its character unless we enter into the long history of Franciscans and Capuchins throughout the world and in Chester. That history begins seven centuries and St Francis’s Chester, is the name both of the present friary church and that of its mediaeval predecessor. We hope that you will find it interesting and be struck by the way Catholic and religious life has ebbed and flowed but never altogether been lost in this country and in this ancient city.

By clicking on the thumbnail pictures in the book they will open full size in a new tab on your browser. Wherever appropriate copyright owners and photographers are listed below each picture. Special thanks to Wikimedia Commons and The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) London for making pictures available for use under the Creative Commons licence.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter One - Origin, Organisation and Life of the Franciscans

1.1 Origin

The present Church and Friary of St Francis have been in Chester since 1875 but, of course, there were Franciscans in Chester long before that. Like most large mediaeval towns in Europe, Chester had a number of houses of different orders of friars.

Their presence is commemorated in local street names - White Friars [Carmelites], Black Friars [Dominicans] and Grey Friars [Franciscans]. The Franciscans originally wore habits of coarse unbleached wool – hence Grey Friars -but at a later date most changed this to 'capuccino' brown (as our present Capuchin friars in Chester). What were friars? The word itself means brothers, but weren't monks, like those in the great Benedictine Abbey of St. Werburgh in Chester (now the Anglican Cathedral), also called brothers? What was and is the difference between monks and friars?

1.2 Organisation

St Benedict © Wolfgang Sauber

St Benedict © Wolfgang Sauber

By far the greatest influence on monastic life in the Western church was that of St Benedict (c.480-c.550). His Rule placed special importance on the power of the Abbot in the community and on stability in the abbey. An old saying made the point: 'a monk out of his cloister is like a fish out of water'. The principal occupation of monks was and is the solemn singing of the Office of Psalms, work in the house or fields, and reading. St Benedict asked that everything necessary (crops, mills, work-places etc) should be within the monastic enclosure to avoid the evil of the monk going beyond it. Hence, abbeys became large self-contained places - often with magnificent churches devoted to the liturgy. St Werburgh's abbey in Chester, for instance, owned all the land up to and beyond the city walls on its Northern and Eastern sides and had revenues from much other property. In the Eastern Church, however, besides this stable monasticism there was another kind of religious life based on wandering and dispossession.

St Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) was the means of bringing this kind of life back into the Western Church. He wanted his followers to be known as Lesser Brothers or Friars Minor and he wanted them not only, like monks, to avoid owning individual property but also to avoid even owning things in common. Franciscans would not live in huge abbeys which were designed, as St Benedict insisted, to make communities self-supporting. Franciscans were to depend upon Providence in the form of gifts or, in necessity, by begging. St Francis was influenced too by another model of religious life - the hermit. At times, he withdrew into complete solitude, like Our Lord Himself, and his followers lived occasionally in small isolated hermitages. Despite this, despite his intense commitment to prayer, and despite his incessant travels far and wide, St Francis remained a townsman forever associated with Assisi. Another mark of Francis and of early Franciscans is an insistence on Penitence which is nevertheless linked to Joy in the Crucified and in every facet of God's creation.

1.3 Life of the Franciscans

If we put all these things together, we begin to see what the new life of "a friar" was. Friars were poor, avoided property, lived in small communities, occasionally in hermitages, but they regularly moved from place to place so as not to acquire that "stability" that St Benedict prized. They lived intense lives of prayer but lived in towns and amidst ordinary people, not in remote places like Fountains Abbey. They lived in obedience, originally to Francis himself, but Francis did not want them to owe lifelong obedience to anyone in the way that monks did to their abbots. How then were the friars to be organised? Francis was the greatest religious genius of his age but he did not have a genius for organisation.

St Dominic © Mattana

St Dominic © Mattana

Fortunately he had a very great contemporary who did have precisely such a genius. He was St Dominic; the two great saints probably met in Rome. Dominic had also stumbled upon the idea of an order of wandering religious. In his conception, they would live like monks but would displace the 'work' ingredient of monastic life by study and preaching. These friars would be organised into provinces with an elected Provincial and a small elected group ('definitors') to look after several friaries each of which would have a Prior. All the provinces in turn would be answerable to a General Chapter and be governed by a Master General. Hence the friars would belong to a world-wide order with clear organisation but one with constant elections, changes of officer, and movements from one house to another. It was this system that was adopted by the Franciscans and all other friars (Carmelites, Augustinians, Servites, Trinitarians etc.) The Franciscans did not like the term 'Prior' so they settled for Guardian (often called Warden in the Middle Ages) and they characteristically emphasised Christ's insistence that those who lead in His Church should see themselves as ministers to others rather than dominating them - hence the head of the Franciscans is called Minister-General. This pattern of organisation works and is still in place today. Every three years, the friars of Chester attend a provincial chapter in one of their friaries. The Dominicans naturally emphasised a monastic timetable as the prerequisite for their life of study and preaching for St Dominic, like Anthony of Padua, began as a devout Canon Regular not as a song-loving gadabout who experienced a dramatic conversion like Francis. Bit by bit, the Franciscans adopted this workable Dominican pattern of organisation with regular recitation of the Divine Office in choir and a fixed horarium, but they were never so monastic in spirit as the Dominicans. On the other hand, the Franciscan nuns founded by Clare, Francis's contemporary and fellow-citizen, lived a wholly contemplative but deeply Franciscan life.

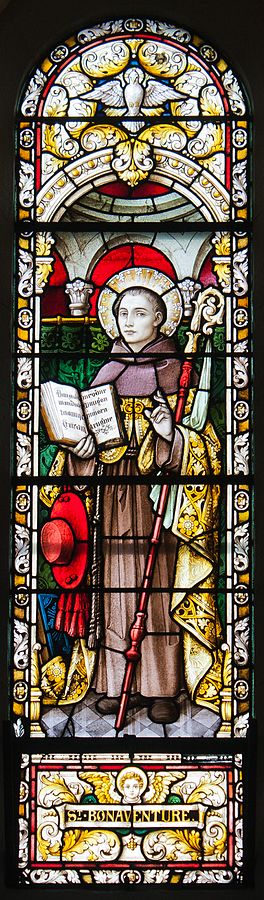

St Bonaventure © Andreas F. Borchert

St Bonaventure © Andreas F. Borchert

What happened to these early Franciscans? The story is one of the most wonderful things that have happened to the Church and yet it often reads like a disaster. There is no straight road in Franciscan history. St Dominic bequeathed his comprehensive model of religious organisation but St Francis was wholly a charismatic figure and, consequently, the Franciscans have served Christ and His Church principally by representing the charisms of Divine Life - unpredictable but fertile. We should not jump to the conclusion, however, that St Francis opposed what is sometimes carelessly called "the institutional Church". On the contrary. It is because St Francis was both absolute in his commitment to the Gospel and to radical poverty and yet humbly committed to the Church and to the Pope, that his movement bore fruit where many other religious movements of this time fell by the wayside.

But there were problems. Some of these were simply born of the staggering success of the new order. Thousands upon thousands joined it and soon there was no town in Europe that had not seen these new wandering ragged brothers fired with the love of Christ and His Gospel. Other problems came from interpreting Francis's legacy and one result of this was that the Franciscans who lived in Chester in the Middle Ages belonged to a different grouping from that which is here today.

St Benedict left a Rule, a model of delicate balances between encouraging fervour and allowing for human weakness, which worked and still works. But Francis left only a short Rule insisting upon absolute poverty and he really wanted his brothers to live directly out of the Gospel rather than in a specified way. The result was that there were, more or less immediately, bitter disagreements and especially a division between those brothers who wanted to live in absolute poverty and preserve the spontaneous character of Franciscan life and those who maintained that, given the numbers now becoming Franciscans, some limited ownership of buildings was inevitable and they should follow a fixed conventual pattern.

It was the genius of that great Franciscan and Minister General, St Bonaventure (1221- 74), to settle this dispute to the satisfaction of most. It is characteristic of Bonaventure that when he was nominated a Cardinal, he was found washing dishes in his friary and told the papal messengers to wait until he had finished. Under Bonaventure, a certain accommodation with property was allowed and he (one of the most brilliant minds of his brilliant age) also decisively countered those who suggested that, unlike Dominicans, it was no business of Franciscans to be learned. Bonaventure managed to convince his friars of this because of his personal holiness and because of his intense and manifest devotion to the memory of Francis. There have always been many different kinds of Franciscan.

This then became the pattern of mediaeval Franciscan life. Friars lived in small houses without parishes in Chester and most major towns. They lived a simplified version of monastic life but moved around from friary to friary, preached in their churches and in market-places, were given licence to hear confessions on a large scale, were usually perceived as the poorest of religious, were as likely to be found teaching and learning in Oxford and Paris Universities as visiting the sick in hospitals.

Friar Roger Bacon © Michael Reeve

Friar Roger Bacon © Michael Reeve

Who has not heard of Friar Roger Bacon? The friars had a good press but not always. On the one hand, they were sometimes accused of lacking their original fervour. On the other hand, not everyone accepted Bonaventure's compromise. Some friars hankered after a more absolute poverty and less conventionally religious life and tried to form groups of their own. Amongst these were some very holy people but also there were some who were mixed up with millennial "spiritual" heresies and odd political movements founded on doubtful prophecies who brought fervent Franciscans into disrepute. Like all religious communities, the Franciscans were very badly hit by the Black Death which wiped out many friaries and made the task of refounding stable religious life very difficult. But Franciscanism persisted and became a major and transforming ingredient of the fabric of Catholic Europe.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Two - The English Franciscans and The Restoration of the Friars

William Fitch (Benet of Canfield) NPG D26038

© NPG, London

William Fitch (Benet of Canfield) NPG D26038

© NPG, London

2.1 The English Franciscans

It was in this way that Capuchins became part of English political and religious life in post-Reformation England. Francis himself had always nursed a missionary ambition and his order never forgot it. England, divided by a Reformation which initially was imposed from above, now became such a mission field. At first, a handful of Englishmen joined the new order. The most distinguished of these was Benet Canfield (William Fitch), a convert from Protestantism who went to Paris, became a Capuchin, and became famous as a master of the spiritual life.

It is odd to think of the powerful French Capuchin, Fr. Joseph du Tremblay, confessing himself to be a disciple of the English friar but he certainly did so. As yet, none of these English Capuchins had returned to England but in 1615 five friars went to Ireland and, a few years later, to Scotland also. The subsequent English Capuchin mission was largely organised from Ireland. Unfortunately, Fr. Joseph in France had his own schemes. King Charles I had married a Catholic, Henrietta Maria, and she was allowed to bring her own Catholic chaplains to the Court. Fr. Joseph arranged for these to be French Capuchins but insisted that the English Capuchins should withdraw to make room for them.

Fr. Joseph du Tremblay © Public Domain

Fr. Joseph du Tremblay © Public Domain

We should not underestimate the importance of this allowed Catholic presence in anti-Catholic London. The French friars made many converts and ministered to Catholics, often in great difficulty, even during the Civil War (they were imprisoned in their friary for much of it). The chaplaincy was revived for a few years at the Restoration. There was then a resumption of native Capuchin activity here directed through the Irish Mission. We hear, for instance, in Chester of Frs. Francis Browne, Bernard McGrath, and Luke Nugent. He died in Chester in 1673 some six years before the martyrdom of St. John Plessington here. It is likely that the two met one another.

Capuchins, in England at this time, of course, went in disguise and often in fear of their lives. For example, another Capuchin, confusingly called Luke Nugent also, wrote in 1701 giving a list of converts that he had made and adds: "I have reconciled others who were in gaols and hospitals of the city, but on account of the great number of spies that are about, and the risks we have to run in those places, I have not been able to collect their names...we go about at night from house to house exhorting the faithful to be steadfast, and administering the sacraments". Yet another, Fr. Bernadine, writes how he said Mass secretly in the Tower of London for imprisoned Catholics, raised alms for five priests imprisoned in Newgate jail and is at present "hiding in a secret place to which many Catholics resort". It must have required immense faith to live day by day like this, but worse was to come.

Fr. Theobald Mathew © Domer48

Fr. Theobald Mathew © Domer48

The end of the Eighteenth Century and, especially the period of the French Revolution, saw attacks on religious houses and religious life on a scale that takes us back to the period when the Capuchins were founded. Capuchins nearly died out in Catholic countries like Italy, Portugal, Spain, and France. There were shortages of manpower everywhere and so all the Capuchins working in England were recalled. One Irish Capuchin, Fr. Arthur O'Leary, worked in London from the outset of the French Revolution until 1802. He was attached to the Spanish embassy - long a centre to which English Catholics could have recourse and now the site of St. James's, Spanish Place. He was buried in London.

Fr Theobald Mathew, the famous Irish temperance campaigner (who was a Capuchin friar) visited England between June and September 1843, but the order’s presence in England was very slight during the first half of the nineteenth century. Yet it was this lowest point of Capuchin life that heralded a remarkable rebirth of religious life throughout Europe and especially in the British Isles.

2.2 The Restoration of the Friars

Viscount Feilding (later Earl of Denbigh) © Public Domain

Viscount Feilding (later Earl of Denbigh) © Public Domain

In 1850, an Italian Capuchin called Louis of Lavagna came to London simply in order to learn the language prior to going to Canada. Whilst here, he was suddenly seized by the idea of reviving English Capuchin life. He was helped by a providential occurrence. Viscount Feilding (later Earl of Denbigh) and his wife were converted to the Church and decided to alter the ownership of a church they were having built at Pantasaph in North Wales to Catholic use. They had been impressed by the simplicity and holiness of some Capuchins that they had encountered in Italy, heard that Fr. Louis and a Tyrolese companion friar were in London, promptly invited them to take up residence in Pantasaph and promised to build them a friary there. Thus, in 1852 four Capuchins came to Pantasaph. These Italian and Tyrolese friars were joined shortly afterwards by a Belgian, Fr. Seraphin of Bruges, and Brother Linus of Gassel, from the Netherlands.

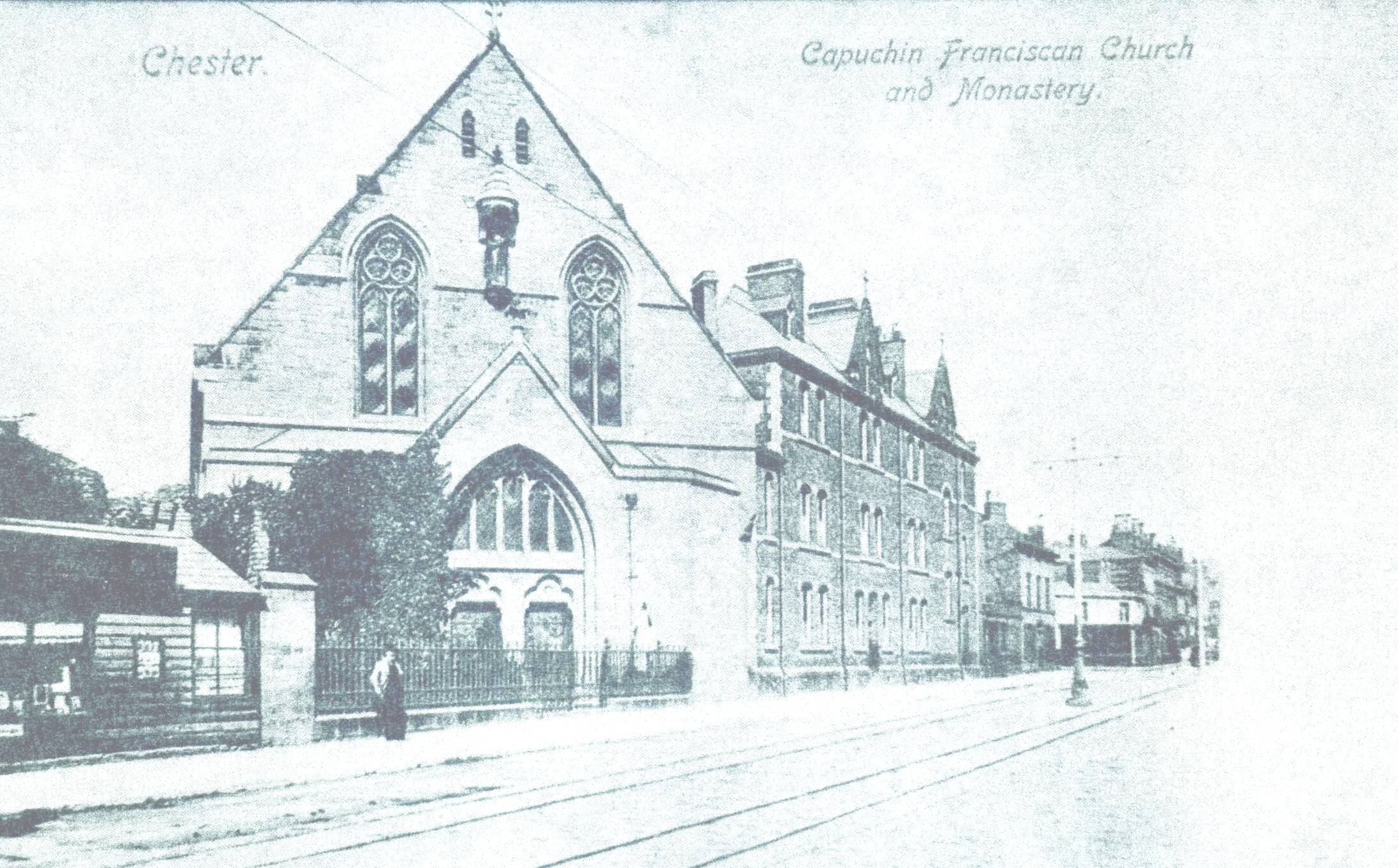

Bit by bit, a large friary was built, the surrounding landscape was laid with trees, and a Way of the Cross, and a mission to the surrounding neighbourhood, were commenced. Franciscans had played an important role in Welsh Mediaeval history; now they were back again. The friars established permanent centres at Chester, Flint, Mold, Holyhead, Pontypool, Colwyn Bay, Penmaenmawr and Mostyn. Of these, Chester and Penmaenmawr became full friaries. Chester continues as such but remote Penmaenmawr after a period as a hermitage used by all branches of the Franciscan Order, is now closed. Soon more friaries were established throughout England and, eventually, but all too briefly, Scotland. All these friaries had parishes attached. This is not a general Capuchin custom but was indispensable at that time when Catholic life was being renurtured in this country.

In recent years, in common with most religious orders in this country and the rest of Europe, the number of Capuchins has shrunk and some friaries have had to be closed. The perspectives brought about by the Second Vatican Council and the increased secularisation of much of the Western world have caused much pondering and it may be that the Franciscan charism in the Church will be renewed in unexpected ways as it has so often throughout its long, magnificent, but never very orderly, history. The main marks of a Capuchin have always been a certain, rather forbidding austerity, poverty, and immense loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church, combined with eccentricity, joyfulness, and complete unstuffiness. These are marks of Francis himself, and his children have always kept alive in the Church a sense of the breathtaking surprisingness of the Gospel. It does not seem very likely that there will be no more Franciscan surprises in the years to come. But we can turn now to the history of the re-established Chester friary.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Three - The Franciscans Return to Chester

The first local mention of the Capuchin presence in Chester comes from the pages of the Chester Chronicle of 24 December 1858.

Image © Chester Chronicle 24 December 1858

Image © Chester Chronicle 24 December 1858

"ORATORY OF ST FRANCIS, CHESTER. - On the 21st of Dec. (the feast of St Thomas), the Capuchin Fathers, from Pantasaph, opened a very neat temporary oratory, public chapel, in Watergate- street, Chester. The Very Rev. F. Seraphine said mass, and the Rev. F. Laurence preached. The collection amounted to £20. The Rev. Canon Carbery, and the Rev. Fathers Elzear, Francis, and Alphonse assisted. There is accommodation for about 100 persons, but it is intended in the course of a few months to build a church, poor schools, and a presbytery, to meet the increasing wants of a poor labouring population of between 3,000 and 4,000 Catholics. The oratory will be conducted like similar institutes abroad. There will be two or more public services every morning, commencing at seven o'clock, and one at seven o'clock every evening. It will be open all day for private devotions"

Image © Chester History & Heritage's Collection

Image © Chester History & Heritage's Collection

Fr Seraphim of Bruges was the Guardian of the Capuchin friary at Pantasaph in North Wales, and he it was who had selected the friars who were to establish the new mission and community in Chester. Canon Carbery was the parish priest of St. Werburgh's, the Catholic chapel already existing in Queen Street. The long-established tradition in the parish that the site of that first oratory was a hired room in Bishop Lloyd's Palace on Watergate Row was recently confirmed by the emergence of photographic evidence. The reasons for the choice of Bishop Lloyd’s Palace are as yet unclear, but it is known that in 1858 the girls’ school operated by the Faithful Companions of Jesus was temporarily housed in “two small rooms in Water Gate Row” whilst a new building was erected for them at Dee House. The coincidence is so strong as to suggest that the opportunity was taken to make use of the premises as a mass centre. The wording on the beam in the photograph reads “ORATORY OF ST FRANCIS”, the in smaller capitals “OPEN FOR PUBLIC & PRIVATE DEVOTIONS”. There is a third line of smaller lettering which unfortunately cannot be read.

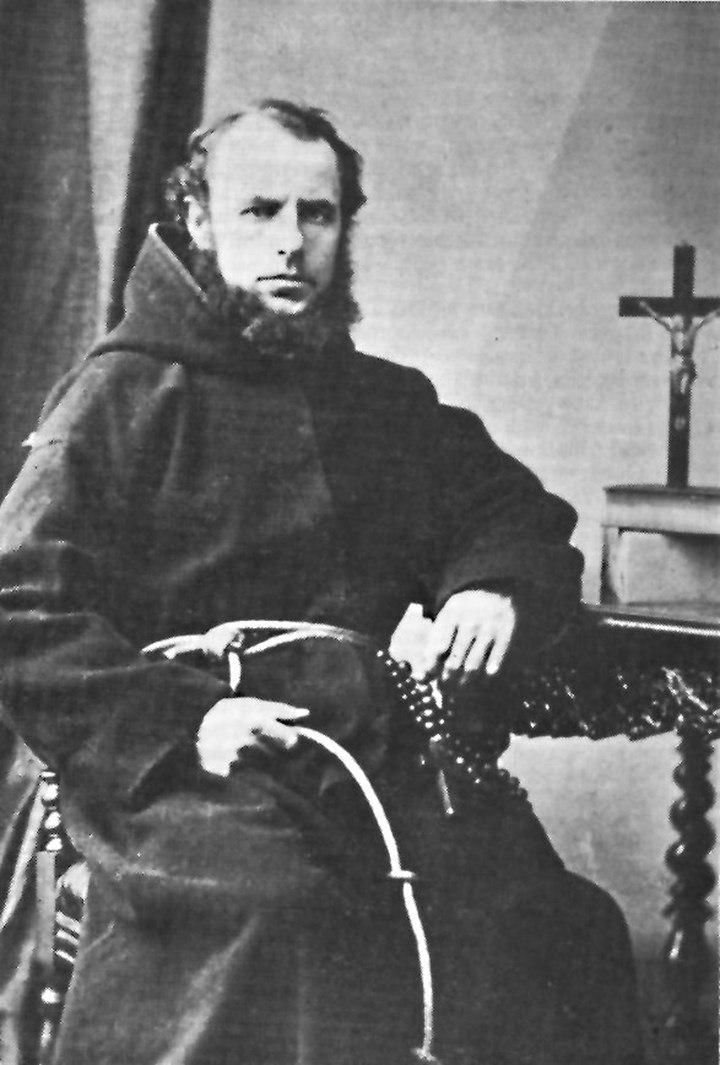

Fr. Venantius Jansen © Sister Mary Winefride Sturman

Fr. Venantius Jansen © Sister Mary Winefride Sturman

That first Capuchin community consisted of three priests, Father Venantius Jansen, from Nieuwenhoorn in Belgium, Fr Engelbert van Dieren, and Fr Nicholas Mazzerini, plus a lay brother, Linus of Gassel. The mix of nationalities reflected that of the Capuchin community in England at the time; it would be some years before native recruits began their ministry. The friars purposely began their mission at the opposite end of the town from St Werburgh's, and actually lived in a couple of small cottages, numbers 13 and 15 Cuppin Street, on the site of the present friary, which is still number 15. The presence of an Italian friar with three Dutch/Flemish speakers in the community may be explained by the fact that there were several shops in that part of the city run by people of Italian origin. Coincidentally or otherwise, that area, between Cuppin Street and Watergate Street, was where the three orders of mediaeval friars (Franciscans, Dominicans and Carmelites) had had their houses before they were suppressed.

The capacity figure of 100 given for the chapel was probably rather optimistic, but the plans of the friars were wildly so. The church was nearly seventeen years in coming, the "presbytery" or purpose-built friary eighteen, and the school twenty-three!

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Four - Timber, Bricks and Mortar

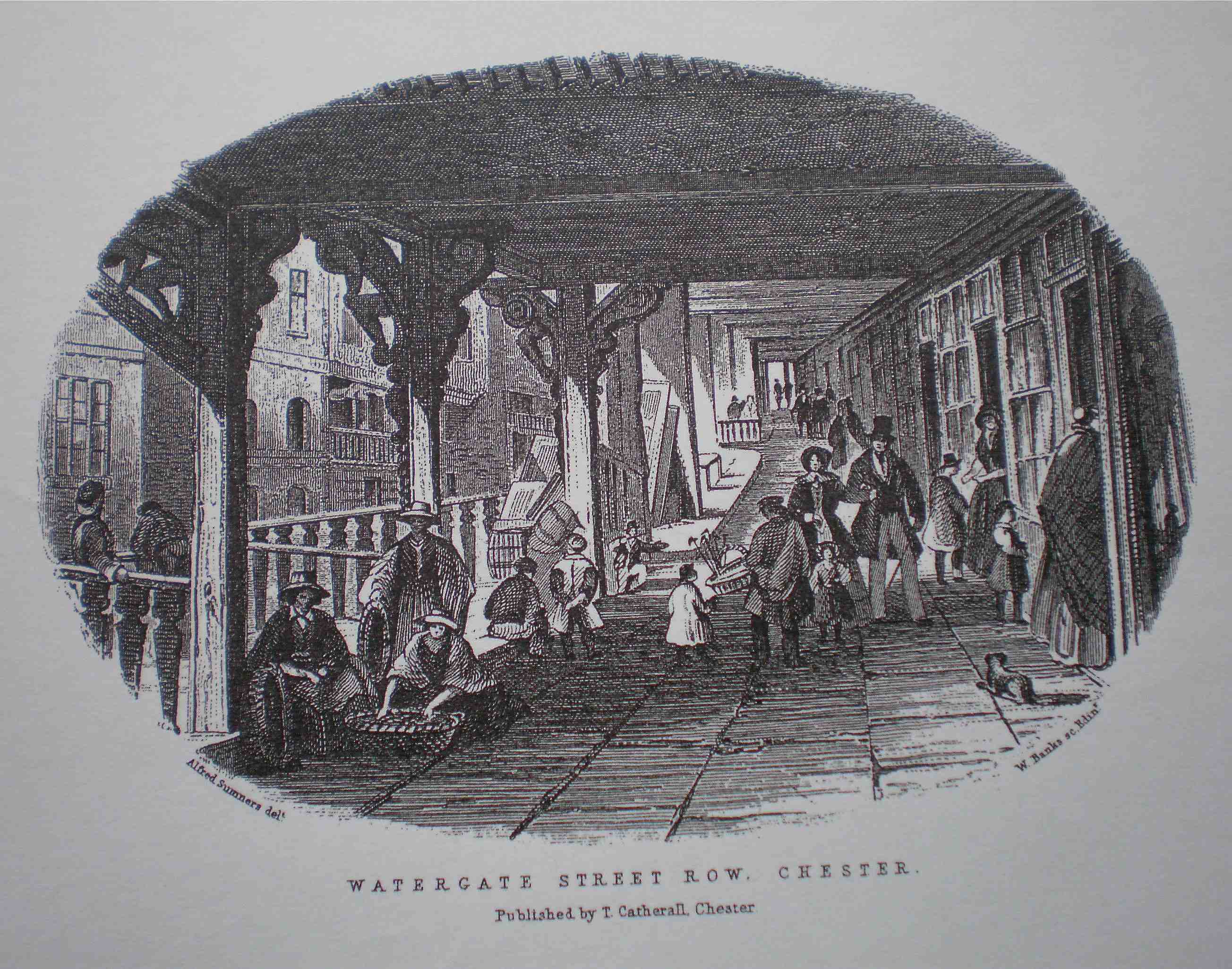

Watergate Row about 1856, looking from Bishop Lloyd's Palace towards the Cross

Watergate Row about 1856, looking from Bishop Lloyd's Palace towards the Cross

Some sources state that the oratory in Bishop Lloyd's Palace was only large enough for a congregation of sixty or seventy people, and that figure must soon have been exceeded. In 1860 services began to be held at the rear of 25 Watergate Row, a building on the same side of Watergate Street as Bishop Lloyd's Palace, but situated nearer the Cross. The premises were occupied by a trunkmaker named James Martin and his family. Mr Martin must have been a keen lay supporter of the friars: he and his wife Margaret appear as godparents in three out of the five baptisms (in October and November 1859) recorded on the first page of our earliest baptism register. (The early registers are now deposited at the Cheshire Record Office for safe keeping).

The chapel behind Mr Martin's shop is sometimes described as a wooden shed, but one source states that the yard was roofed over. Whatever the case, the new structure could accommodate three hundred people.

Grosvenor Street in the 1860s

Grosvenor Street in the 1860s

The next stage was to look for a site for a purpose-built church, and in 1862 a suitable piece of land was found between Grosvenor Street and Cuppin Street. It belonged to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, an Anglican body now called the Church Commissioners. The Commissioners were selling off small parcels of land in Chester around that date, presumably as part of a process of rationalisation, and sold the site to the Capuchins. Donations were received from, among others, the Earl of Denbigh, Sir Thomas Stanley of Puddington Hall, and William Topham of Broughton Hall (the proprietor of Aintree Racecourse). The foundation stone of the new church was laid on 23 September 1862 by Bishop Brown of Shrewsbury.

In keeping with the friars' original declared aim "to meet the increasing wants of a poor labouring population" the site for the church and the friars' own accommodation was in one of the poorer quarters of the city at that time. The feeling of optimism that must have marked the foundation was destroyed shortly after when the building contractor went bankrupt and no-one else could be found to continue the work on the basis of the original contract. As if that were not enough, an earthquake occurred in Chester in October 1863, which affected the partially completed building so badly that the east gable had to be completely dismantled. This had just been rebuilt and the church (except for the sanctuary) reroofed, when further disaster struck. On 3 December a hurricane hit the building and more or less wrecked it. The City authorities declared it unsafe and ordered its demolition. The following account, taken from the 1869 edition of The Stranger’s Handbook to Chester, by Thomas Hughes (p87-88) gives a brief description of the situation, as well as an insight into attitudes prevalent at the time, in some quarters at least.

'Beyond [Bunce Street], upon the opposite side [of Grosvenor Street], is the recently-built Church, already a ruin, of the Romanist brotherhood of St. Francis, the first stone of which was laid in 1862.'

Spirits must have been terribly low among the friars and their congregation, but on 16 June of the next year (1864) a temporary wooden chapel with a capacity of 500 was erected on the site. It was to be the spiritual home of our congregation for the next decade.

Some idea of the workload of the friars during this period can be gleaned from the entry for the church in the 1870 Phillipson and Golder's Directory of Chester. Only two priests (Fr Venantius and Fr Pius) are listed, and the times of services were as follows:

Sundays and Holidays of Obligation, Mass, 7.30, 9 and 11am; Catechism at 2pm; Baptism at 4pm; Vespers, Sermon and Benediction, at 6.30 pm.

Week days, Mass at 7 and 7.30am; Evening Prayers at 7pm Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, Rosary and Benediction at 7pm; Fridays, Stations, 7pm.

Chester Music Hall circa 1869

Chester Music Hall circa 1869

After 15 years as Guardian, Fr Venantius moved on to missionary work in India and was replaced by Fr Pacificus Perucci of Camerata. 15 years is a record term for the Chester community, but those were unusual times. Fr Pacificus immediately set about replacing the wooden chapel with a more substantial building. Of course a point was reached where the wooden chapel had to be dismantled. This occurred at the end of November 1874 and in the interval the friars celebrated Sunday masses at the Music Hall, a building situated between St Werburgh Street and Northgate Street (now [2017] the premises of Superdrug).

Interior of Chester Music Hall

Interior of Chester Music Hall

As the illustration shows, it would have been perhaps surprisingly suitable for holding church services. The building was originally, in mediaeval times, the Chapel of St Nicholas, and later served as the parish church of St Oswald. During the week mass was celebrated in the private chapel at the friars' house, 13 Cuppin Street.

The map showing the Grosvenor Street site was published in 1875, but surveyed in 1872. The colouring convention used by the Ordnance Survey during that period was that buildings of stone or brick were shown in carmine red, whilst those of metal or timber were shown in grey. This is the only depiction of that wooden chapel in any form so far discovered.

Ordnance Survey 1:500 town plan Chester Sheet XXXVIII.11.22 (1875) © Crown copyright

Ordnance Survey 1:500 town plan Chester Sheet XXXVIII.11.22 (1875) © Crown copyright

Reproduced with the permission of Cheshire Archives and Local Studies

Reproduced with the permission of Cheshire Archives and Local Studies

The end of years of temporary arrangements came on 29 April 1875, when the new church, dedicated like its pre-Reformation predecessor to St Francis of Assisi, was solemnly opened. This was no low-key affair: those present included Cardinal Manning, Bishop Brown, Bishop Hedley (the Auxiliary Bishop of Newport), the Earl of Denbigh and the Mayor of Chester. Following the church service a festive lunch for 200 guests was held at the Grosvenor Hotel, presided over by the Cardinal.

Having attended to the accommodation of their flock, the friars were now in a position to look for a more suitable home for themselves. The two small cottages in Cuppin Street where the community had established itself at the start of its ministry must have been cramped and inconveniently laid out for their purposes. The foundation stone of a purpose-built friary, situated next to the church on Grosvenor Street, was laid on 3 August 1875, and the building was solemnly opened on 19 July 1876. The opening was preceded by a solemn High Mass. In his sermon Fr Pacificus thanked all those who had contributed towards the £2,000 building costs of the friary and enabled the friars "to be seen again in their own monastery, in the ancient city of Chester, trying by their simplicity and fervour, both among the rich and the poor, to gain souls to Jesus Christ". Following Franciscan practice, the new house was then left open to the public for a week, so that all who wished might visit it. At the time, this was probably a very practical move also, as it would have given Christians of other denominations, with little concept of the life of monks or friars, a chance to see what the inside of a friary was like and so rid themselves of any of the misconceptions common at that time.

The friary, like the church, was designed by James O'Byrne, and among those contributing to its cost had been the Duke of Norfolk, the Earl of Denbigh (who had laid the foundation stone), and a number of prominent local Catholic families, including the Tophams, the Tatlocks and the Burtons.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Five - Growing Responsibilities

Even after the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy here in 1850, England and Wales were still regarded to some extent as mission territory, and there were nothing like as many Catholic churches in existence as there are today. The Chester Capuchin community was responsible for a wide area: all the western part of Chester and out into the rural areas on that side of the city, and they soon began to look for ways to extend their service to it. In 1862 the friars started a mass centre at Saltney in a loft above a stable. In 1877 the Duke of Westminster gave a parcel of land for a Catholic school to be built, and so the mass centre became a school - chapel. It was served from the friary until 1913, when it was handed over to the diocesan clergy, and is now St Anthony's parish (a suitably Franciscan dedication) in the diocese of Wrexham.

St Francis Church 1904

St Francis Church 1904

Like all other Catholic faith communities in England in the 18th and 19th centuries, St Francis's itself started as a 'mission', only acquiring permanent buildings over the course of time. The granting by Rome of the change of status from missions to parishes only came into force on 12 November 1918. Returning to Grosvenor Street, from the door of the church one can look across the parade ground to Chester Castle where St John Plessington was imprisoned three centuries ago. In the 1883 Slater's Directory of Cheshire and Liverpool Fr Pacificus is listed as the Roman Catholic chaplain to the military prison there. In the 1892 Kelly's Directory for Cheshire we find Fr Anthony Brennan of Tasson (the then Guardian) listed as Roman Catholic chaplain to what was then known as the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum in Liverpool Road, Upton. The establishment of mission "out-stations" and the provision of chaplaincy services were to be part of the life of the Chester community until well after the Second World War. Indeed the link with the former asylum, now the Countess of Chester Hospital, remains unbroken to this day.

Interior of St Francis Church from the porch

Interior of St Francis Church from the porch

Interior of St Francis Church from the gallery

Interior of St Francis Church from the gallery

Fr. Angelo, Pacificus and Nicholas

Fr. Angelo, Pacificus and Nicholas

This photograph shows from left to right Fr. Angelo, Fr Pacificus and Fr Nicholas.

- Fr. Angelo - Assistant on the Parish, 1875 - 1883

- Fr. Pacificus (Perrucci) of Camerata - Second Guardian of Chester, 1873 - 1879

- Fr. Nicholas (Mazzerini) of Carpegna - Third Guardian of Chester, 1879 - 1882

By contrast with Fr Venantius's record 15 years, the normal period of holding office among Franciscans is three years, with the possibility of re-election for a further three. Fr Pacificus was Guardian from 1873 to 1879, being then succeeded by Fr Nicholas of Carpegna, but he returned (one hopes after a well-earned rest) from 1882 to 1885. His successor this time was the first native Briton to be Guardian at Chester - Fr Modestus of Glasgow - and he was succeeded in 1888 by Fr Bernard of Chester, the first of several 'local boys' to return as Guardians or members of the community here.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Six - St Francis's School

In the early days of the mission, Catholic children living in the area served by the friars attended St Werburgh's school, but the foundation stone of a school for the parish was laid by the Earl of Denbigh on 5 June 1881. The premises opened on 20 May of the following year, with accommodation for about 300 pupils. In Chester, at that date, compulsory education ended when the child reached the age of 13.

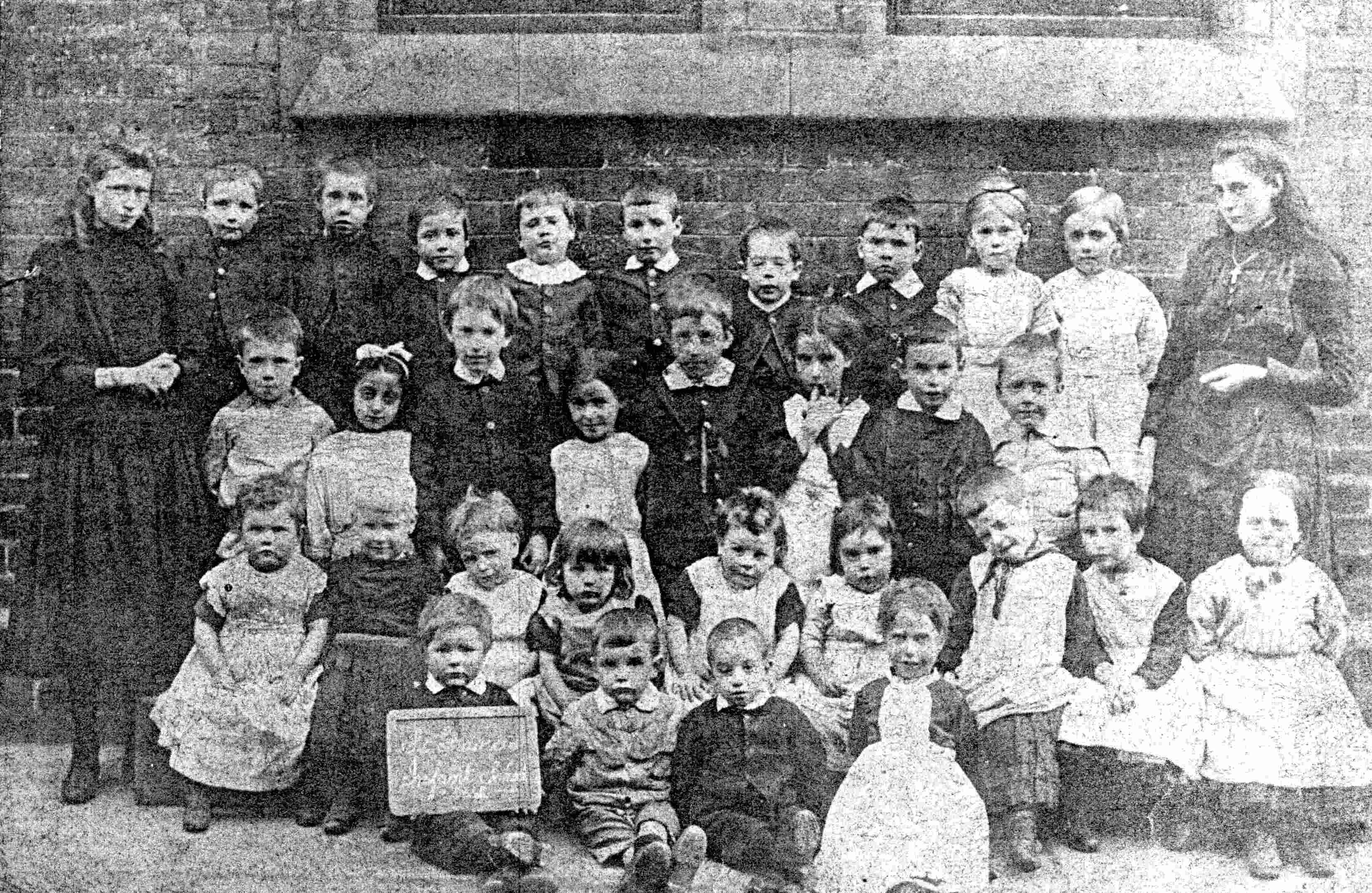

St Francis School in 1890s

St Francis School in 1890s

In the 1883 directory, a Roman Catholic school in Cuppin Street is mentioned, with 'the Sisters' (ie the Faithful Companions of Jesus from Dee House) as teachers, as they were at St Werburgh's also. However, in 1890 a Miss Kirk is listed as mistress, and so lay headship became the norm. In the 1892 directory, the school is listed as St Francis Catholic School, with Miss Teresa Kirk as mistress and Miss Mary Ellen Murphy as infants' mistress. The school is described as "mixed and infants", with places for 160 mixed and 148 infants, but the average attendance is given as 88 mixed and 60 infants, i.e. less than 50% of the theoretical capacity.

Whether this meant that the places available were not all filled, or whether there was a high rate of absenteeism, is not clear. However, even 148 children must have been a burden for Miss Kirk and Miss Murphy, even assuming that they had the assistance of a pupil-teacher or two.

The ratio of teachers to pupils may have improved by 1905, for in the directory for that year, although we are not told the numbers of pupils, the headmistress was Miss Bianchi, and she had as assistant mistresses Miss M Dooge, Miss Daly and Miss Handley. If there was an attendance problem it obviously persisted, for in the 1906-7 directory the school's accommodation is quoted as 303 and the average attendance as 129. Miss Bianchi's initial, incidentally is revealed as E. Miss Dooge went on to become Head Teacher by 1909, when the accommodation figure is given as a perhaps more realistic 228, and the average attendance as 150. The school's designation in that year was 'St Francis RC Private School (Mixed)', an indication that it was not recognised by the local education authority. No information, unfortunately, is given as to how it was funded, but on 29 October 2000 Miss Ellen Byrne, a lifelong parishioner whose mother started teaching at the school in 1909, told Peter Bamford that her mother once told her that at some unspecified date the then Guardian had sent 'the brother' (i.e. the laybrother who looked after the domestic needs of the community) through to the school to tell the staff that there were insufficient funds to pay their salaries, and would they mind waiting? Miss Byrne surmised from this that the school was being run purely out of parish funds. The private status continued under a succession of Head Teachers (Catherine O'Keefe, Marianne O'Sullivan, Miss O'Neill) until after the First World War, when recognition was granted by Chester City Council. In 1923, under the Headship of Mrs Davis, accommodation was still for 228, and average attendance was 128.

The granting of recognition may have been due to the fact that in 1919 two houses in Cuppin Street and the court behind them, extending to Grosvenor Street, were bought and demolished, which allowed the school playground to be extended. Even with those and other improvements, the school buildings, like most of those built around the same date, were considered inadequate by post-Second World War standards.

The Chester Catholic May 1961

The Chester Catholic May 1961

In 1972 Chester City Council, the Local Education Authority, decided on a policy of three-stage education. Schools were to be first, middle or high in ascending order of the age range they catered for. St Francis's became a first school feeding St Clare's Middle School, a modern building in Hawthorn Road, Lache. This arrangement ended when responsibility for education in Chester was transferred to Cheshire County Council on local government reorganisation in 1974, and a reversion to the more general primary - secondary split took place. With a diminished population in its catchment area, and inadequate buildings, the school eventually closed in 1976. The classrooms, however, still survive as the Parish Hall and the rooms above, all still in use for a variety of purposes. Many testify to the excellent teaching and sound spiritual foundation they received at the school. Among many excellent teachers we should perhaps single out Jack Wildig, a lifelong Capuchin at heart who devoted his whole life to St Francis's parish in its myriad activities.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Seven - The Parish Club

This institution, for so many years a prominent feature of parish life, probably had its origins in the parish's branch of the Catholic Young Men's Society, which was in being by 1893. The Chester directory for that year tells us that its General Meeting was held on the first Wednesday of each month, at 8 pm, in the Schoolroom.

The directory for 1906-7 shows that the club was by then in full operation:

- Spiritual Director: Rev Fr Dominic

- President: Mr W H Jarvis

- Vice-President: Mr W Hopton

- Hon Secretary: Mr W Byrne

- Secretary: Mr Wm Clarke

- Library and Reading Room Librarian: Mr J Fox

- General Meeting held on the 1st Sunday in the month at 8.30pm

- Guild Meeting on last Sunday in each month

- Tontine every Saturday from 8.30pm to 9.30pm

A tontine was originally a scheme whereby a number of people each paid an agreed amount into a common fund, and the last surviving member of the group was entitled to the whole amount. The weekly occurrence, especially on Saturday (pay day), of the "Tontine" here suggests it was some kind of benefit club. The already impressive range of facilities continued to expand: in the 1909-10 directory there is mention for the first time of a Steward (Mr E Eccles), suggesting that a drinks licence had been obtained, and we are also told that "Gaelic Classes are held on Mondays and Thursdays at 8.30 pm in a room adjoining the Club: Beginners' Class on Mondays - Teacher: Mr Francis Young". The Gaelic was presumably Irish.

As well as all that, the entry for the club in the 1912-13 directory contains the following: "Debating Society: Debates are held during the Season - Hon Sec: Mr C Logan".

Probably the best picture of the extent of the club's scope is that provided by the directory for 1915-1916:

- Spiritual Director: Very Rev Father Vincent

- President: Mr J Holmes

- Vice-President: Mr C Creighton

- Hon Secretary: Mr E Berney

- Steward: Mr W Woodward

- General Meeting held on the 1st Sunday in the month at 8.30pm

- Library, Reading and Recreation Rooms

- Young Men's Society Diocesan Council

- Secretary: Mr T Waldron

- Branch Representatives: Messrs Thos Rafferty & H J Williams

- National Catholic Benefit & Thrift Society (Approved No 242, Head Office: Liverpool), St Francis' Branch (Registered No 282):

- Chairman: Mr H J Williams

- Treasurer: Mr E Berney

- Secretary: Mr P C Byrne, 24, Vernon Road. Meetings for consideration of claims, payment of benefits, &c, every Tuesday Evening.

- Cheshire District Council

- District Secretary and Member of joint Board of Management: Mr Terence Waldron, 2, The Headlands

The Gaelic classes and the debating had stopped, but the First Day on the Somme had still to dawn, conscription had still to be introduced, and the full effects of the First World War were yet to be felt. The entry in the 1917-18 directory, whilst giving much the same information, concludes with the poignant sentence "40 per cent of members on active service".

As succeeding directories show, the club continued to flourish during the years between the two World Wars, though no doubt it was affected to some degree by the arrival of radio and the "talkies". Reading between the lines of the directory entries, a picture emerges of what must have been a most useful facility for the men of the parish. Indeed, given the economic situation between the wars, it may have been a lifeline for some of them. The obvious attraction of the club was that it had a licensed bar, but at least the profits from that would have been ploughed back into the parish. Perhaps also male parishioners' wives looked more kindly on their spending an evening in the parish club than in one of the nearby pubs. But it is important to remember that at that time provision of all kinds by central and local government was on a much smaller scale than has been the case since the Second World War. So apart from the opportunity to have a drink, men could avail themselves of the recreation rooms and library. On a more serious note, they could save a little money via the Benefit Society and presumably claim on its funds if in need. In the days before the welfare state, the value and importance of organisations like this must have been enormous.

The club, like other parish institutions, was hit hard in the 1950s and '60s: by the demolition of housing within the parish, the arrival of television and by increasing car ownership which gave people the opportunity to travel further afield in their leisure time. Eventually it ceased to be viable and the premises, in Union Place just off Cuppin Street, were closed.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Eight - More on Mission

We have already seen something of the chaplaincy services provided by the friars, and this aspect of their work in Chester was to expand over the years. With a large military presence literally across the road from the church, it was only to be expected that demand would come from that quarter at an early stage.

In the 1876-7 Phillipson and Golder's Directory of Chester, the 9am Sunday Mass at St Francis' is described as "military", presumably indicating that it was attended as a church parade by the Catholic members of the garrison at Chester Castle. The Military Mass ceased not long after the First World War.

8.1 Hospital Chaplaincy

Cheshire Lunatic Asylum © Wellcome Library, London

Cheshire Lunatic Asylum © Wellcome Library, London

In 1928 there were four priests stationed at St Francis'. An entry in The Catholic Manual of Instruction and Official Guide for that year shows that their schedule was similar to that of twenty years or so earlier, but the note "Telephone Chester 38" shows that the friars had not been slow in embracing the new technology of the day. The entry goes on to state that, apart from the services to the Castle and the mental hospital which were noted earlier, the friars were now providing chaplaincy services to the Royal Infirmary, the Isolation Hospital, and the Cottage Homes. The Infirmary has recently been demolished and housing built on the site: the friars continued to serve it until its closure.

The Countess Of Chester Hospital © Dennis Turner 2005

The Countess Of Chester Hospital © Dennis Turner 2005

Hospital provision in Chester is now based at the Countess of Chester site, of which the old mental hospital forms a part. The friars continue to have a regular ministry there. The Isolation Hospital was on Sealand Road. In addition to the Countess of Chester Hospital, the friars currently also provide chaplaincy services to the Grosvenor Nuffield Hospital, a private hospital located on the Wrexham Road.

8.2 Chaplaincy to Sisters

'30 Union Street' is an unremarkable address, but it was home over a seventy year period to sisters from three different orders, all of whom were provided with convent chaplains by the Chester Capuchins. The convent was originally built in 1913 for the Little Sisters of the Assumption, an order whose work is the nursing of the sick of the working classes of all denominations in their own homes. During the First World War some wounded Belgian soldiers were brought to Chester and the Sisters turned their convent into a small hospital to care for them. In recognition of this work the Superior was later awarded the Medaille de la Reine Elisabeth by the King of the Belgians. After the Second World War many of the services which the Sisters had provided were taken over by the Welfare State, and they left Chester in 1956.

After being vacant for two years, 30 Union Street was occupied in 1958 by the Sisters of Charity, who engaged in pastoral work and teaching around the city until 1981 when they closed the convent, the Sisters who were still teaching locally commuting from their convent at Rock Ferry.

Late in 1982 some sisters of the Congregation of Adoration Repatrice came from Liverpool and moved into 30 Union Street. Their chapel was open for perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. They left after some years, and the building was sold for housing development.

The friars' work with these communities consisted principally of the celebration of daily Mass and the hearing of confessions, but they were able to help in other ways too. Responsibility for communities of women still continues in that the friars have for some years provided chaplains to the Benedictine nuns who have a house in Curzon Park across the river. The house was earlier used by Ursuline sisters but has had a new and larger chapel built for the Monastic Office.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Nine - Daughter Churches

9.1 St Clare's Church, Lache

St Clare's Church, Chester © St Clare's Website

St Clare's Church, Chester © St Clare's Website

We have already looked at the growth of Saltney into a fully-fledged parish. Similar processes occurred in more recent years. The cause was the building of more housing on the western outskirts of Chester, commencing with the Lache council housing estate in the 1930s. The pace increased after the Second World War, and this was responsible for major changes in St Francis' parish, the effects of which are still being felt.

To provide for Catholic residents of the Lache estate, a church dedicated to St Clare was opened on 8th December 1960. Initially it was a Mass centre rather than an independent parish, and was served by the friars. Even after it became a parish in its own right, in 1969, the friars continued to staff it until 1980, when it was handed over to the diocese of Shrewsbury.

For further information visit their website by clicking this link St Clare's Church.

9.2 St Theresa's Church, Blacon

St Theresa's Church, Chester © Rev. Gervase N. Charmley

St Theresa's Church, Chester © Rev. Gervase N. Charmley

During the 1950s the friars had worked on the other new council estate, in Blacon, which was situated in St Francis' parish. They carried out a census of the Catholic population, and when Blacon was handed over to the diocese to become a separate parish in 1956 they provided a site for the church and presbytery and £1,000 towards the cost. The new church, dedicated to St Theresa of Lisieux, opened in December 1959.

For further information visit their website by clicking this link St Theresa's Church.

For information on all of the Churches in Chester visit Steve Bulman's excellent website 'The Churches of Britain and Ireland' by clicking this link www.churches-uk-ireland.org.

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Ten - Work With The Homeless

10.1 Introduction

The foregoing sections may seem to be a tale of decline: the parish shrinking in size and its institutions closing. However, as one door closes, another opens and just when things must have seemed at their blackest it became evident that homelessness was becoming an increasing problem in the city. The Franciscans are wanderers by vocation and have always had an understanding of the dispossessed.

10.2 Chester Aid to the Homeless (CATH)

CATH Sleepout Poster © CATH 2016

CATH Sleepout Poster © CATH 2016

Chester Aid to the Homeless (CATH), a non-denominational charity, came into being in 1972, and one of its founders was the late Fr Crispin Jones, who was part of the Chester community then and for many years afterwards. CATH's original aim was to raise funds for a night shelter (later named "Crispin House"), but its work has expanded greatly since those early days. During much of his nine years as Guardian, Fr Timothy Dowling was secretary of CATH, and received a civic award for his work. He was responsible for CATH's major annual fundraising event, the sponsored sleep-out, which traditionally takes place in the friary car park on the night of the first Friday in December. Visit their website for all the latest information on the services they provide, fundraising and events http://cath.org.uk/.

10.3 Churches Together in Chester

© Churches Together in Cheshire

© Churches Together in Cheshire

For some years during the winter months the parish hall accommodated a soup kitchen operated by 'Churches Together in Chester', which provided a hot meal Monday to Friday for homeless people. Of more recent years, CATH has become a more professional organisation and operates in close-co-operation with the local council in providing services to the homeless. The friary and parish still maintain a connection with the work. The website for Churches Together In Cheshire has information about all the groups in Cheshire http://www.cheshire-churches-together.org.uk/.

10.4 Cheshire Record Office Repository

If you would like to find out more information about 'Churches Together in Chester' a visit to the 'Cheshire Archives & Local Studies', Cheshire Record Office, Duke Street, Chester, CH1 1RL will give you access to the following documents;

| Ref | Date | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| D 6074 | 1968-1996 | Chester Council of Churches records | View |

| D 6768 | 1982-2001 | Churches Together in Chester, Soup Kitchen records | View |

| D 6775 | Oct 1991-Nov 2000 | Churches Together in Chester Minutes, reports, accounts etc | View |

| D 7023 | 1988-2005 | Churches Together in the City Centre of Chester records | View |

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Eleven - Modern Times and Twenty-first Century Developments

11.1 Modern Times

We have already noted the spread of Chester to the west and the carving of new parishes out of St Francis'. A further effect on the parish was that the sub-standard housing which the new estates replaced was demolished, being replaced mainly by commercial property. This has meant a great reduction in the number of people living within the revised parish boundary, though in recent years the building of more private housing closer to the city centre has reversed the decline and begun to alter the patterns of city life. Since the Second Vatican Council changes have been made in the layout of the church to bring it into line with its teachings: the reordering has been carried out in a sympathetic manner preserving the quiet and spiritual character of the building. Another consequence of the Council was the setting up of a Parish Council in the early 1960s: the Council is still in being. In the 1980s the 1876 friary building was disposed of (it became, suitably enough, a hostel for homeless men initially, and more recently was turned into student accommodation) and the friars moved into a smaller modern building on the other side of the church,largely converted from the modern portion of the former school premises. The friars are, literally, back where they started in 1862, but the new building is much better suited to the needs of a present-day community.

The church attracts many people from outside the parish to its Masses, on Sundays and perhaps even more during the week, and serves as a meeting place for several Catholic (and other) organisations which function on a city rather than a parish basis. Its role at the present is that of a centre offering Franciscan spirituality at the heart of a busy commercial, administrative and tourist city. Some sign of its witness throughout the period of its restoration in the city is that, as in mediaeval times, there have been many vocations to the religious life which started here. There have been at least nine vocations as nuns, especially to the Poor Clares, nine have become Capuchin friars, and at least one secular priest (Fr. Phillip Dwerryhouse).

11.2 Twenty-first Century Developments

Without a doubt the most radical change in the parish this century has been the growth of a large Polish congregation following Poland’s accession to the European Union on 1 May 2004. There is nothing new about immigrant parishioners: earlier chapters of this book have shown that the first Capuchin community here was made up of Belgians and Italians, and that they were ministering to a congregation which included Irish and Italian immigrants. Later decades saw Belgian refugees during the First World War and an earlier influx of Poles during and after the Second. A great strength of a parish served by an international religious order is that it can call on foreign priests (with the necessary language skills0 more easily than a conventional diocesan parish. Thus, from the early years of present-day Polish immigration, Polish friars have been seconded to care for their countrymen and women in and around Chester. Of recent years, the practice has been for the Guardian of the friary to be a native English speaker and the Parish Priest Polish (albeit with a good command of English). At present (20017) the congregation at the Polish masses outnumbers that at the English.

The other major event was the fire which broke out on the night of Monday 30th July 2012. The emergency services were called just before 10pm, and according to the Chester Chronicle, it took 18 firefighters and 5 fire engines four hours to extinguish the blaze. They finally left just after 6 am, having carried out safety inspections of the building. Fortunately no-one was injured. The fire had started in the sacristy: it did not cause too much damage of itself, but part of the roof had to be removed in order to get at the source of the fire, and there was extensive smoke damage to the main body of the church. As a result, a full redecoration scheme had to be carried out. Previous chapters have told of the mighty wind and the earthquake that struck the church in its early days. Now we have had the fire; we await the still small voice! (Check out 1 Kings 19: 11-13 by clicking here if that doesn’t make sense.)

11.3 Redecorating St Francis Church

A View of The Main Altar

A View of The Main Altar

The Ceiling of the Church

The Ceiling of the Church

Close-up of The Main Altar

Close-up of The Main Altar

View from Back of Church

View from Back of Church

Left Hand Side of Church

Left Hand Side of Church

Right Hand Side of Church

Right Hand Side of Church

The Back of the Church

The Back of the Church

[Back to Contents]

Chapter Twelve - Guardians of Chester Friary and Parish Priests of St Francis'

Among Franciscan friars it was usual for centuries for a brother to be given a new name on entry into the Order and thereafter to be known by that name and his birthplace. The practice lasted among the Capuchins until the last few decades. Among St Francis' first group of followers, there were only two priests, Brother Sylvester and Brother Leo. Reverting to early practice the Capuchins recently dropped the distinction between "Father" for friars who were ordained priests and "Brother" for lay brothers, and are now all referred to as "Brother", among themselves at least, though old habits die hard among their parishioners. Similarly, it is now once again possible for a lay brother to be appointed Guardian of a friary.

In a large friary such as Pantasaph, the roles of Guardian of the Friary and Parish Priest will generally be filled by two different friars, but in a smaller friary one friar will carry both sets of responsibility, as has been the case at Chester.

| Guardian of the Friary and Parish Priest | Date |

|---|---|

| Venantius of Nieuwenhoorn | 1858-1873 |

| Pacificus of Camerata | 1873-1879 |

| Nicholas of Capegna | 1879-1882 |

| Pacificus of Camerata | 1882-1885 |

| Modestus of Glasgow | 1885-1888 |

| Bernard of Chester | 1888-1889 |

| Anthony of Tasson | 1889-1892 |

| Fidelis of Liverpool | 1892-1895 |

| Bernardine of London | 1895-1896 |

| Ambrose of London | 1896-1898 |

| Seraphin of London | 1898-1902 |

| Fidelis of Liverpool | 1902-1905 |

| Dominic of Derry | 1905-1908 |

| Seraphin of London | 1908-1911 |

| John Capistran of St Helens | 1911-1914 |

| Vincent of Liscard | 1914-1919 |

| Dominic of Derry | 1919-1922 |

| Wilfred of Brooklyn | 1922-1925 |

| Andrew of London | 1925-1931 |

| Stanislaus of Malta | 1931-1934 |

| Pacificus of Amble | 1934-1937 |

| Andrew of London | 1937-1943 |

| Victor of Johnstown | 1946-1949 |

| Aidan of Bolton | 1949-1954 |

| Edward of Southport | 1954-1957 |

| Ignatius of Washington | 1957-1960 |

| Callistus of Bradford | 1960-1963 |

| Ernest of Chester | 1963-1969 |

| Vincent of Boyle | 1969-1973 |

| Simon of London | 1973-1977 |

| Aelred of Middlesbrough | 1977-1981 |

| Killian of Bradford | 1981-1984 |

| Michael Mcintyre of Manchester | 1984-1986* |

| Timothy Dowling of Manchester | 1988-1997 |

| Francis Maple of Lahore | 1997-2005 |

| Gordon Pesterfield of Boston | 2005-2008 |

| Prins Casinader | 2008-2011 |

| Andrzej Tomkiel (Parish Priest) | TBA |

| Jarek Konopko of Smolany (Parish Priest) | 2011-2017 |

| Michael Welch of Dudley (Laybrother – Guardian) | 2011-2014 |

| Parick Mulligan of Cavan (Laybrother - Guardian) | 2014-2017 |

| Jarek Konopko of Smolany (Guardian and Parish Priest) | 2017 - 2020 |

| Jinson Devasya (Administrator) | 2021 - |

| Michael Welch of Dudley (Guardian) | 2021 - |

* Fr Michael died suddenly during his Guardianship in the Sacristy, having just said Sunday Mass. Until the next Chapter, the parish was overseen by the Vicar, Fr Ninian Currie.

We hope you have enjoyed this short account and that you will pray for the fruitful continuance of the Franciscan presence in this ancient city. We cannot better conclude it than with the last words of Fra Ruffino's sixteenth-century Capuchin Chronicle:

To the praise and glory of Our Saviour Jesus Christ and the honour of our Father S. Francis.

Amen.

[Back to Contents]

St Francis Church in 1904

St Francis Church in 1904 St Francis © Tetraktys

St Francis © Tetraktys School Children in the 1960s

School Children in the 1960s